Sous les pavés, la plage…

(Under the paving stones, the beach…)

Or a reflection on the diffuse condition of the local in the globalised world. By Fábrica de Paisaje

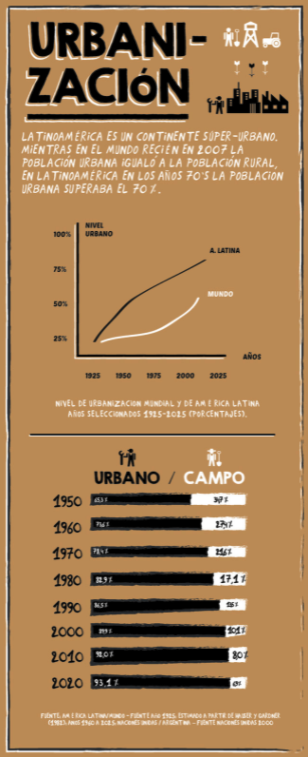

The local and the global constitute, in a broad and long-term reading (because they are intimately related to changing factors such as the ecosystem, the climate, the landscape), historically transformable conditions, or in other words, concepts in movement.

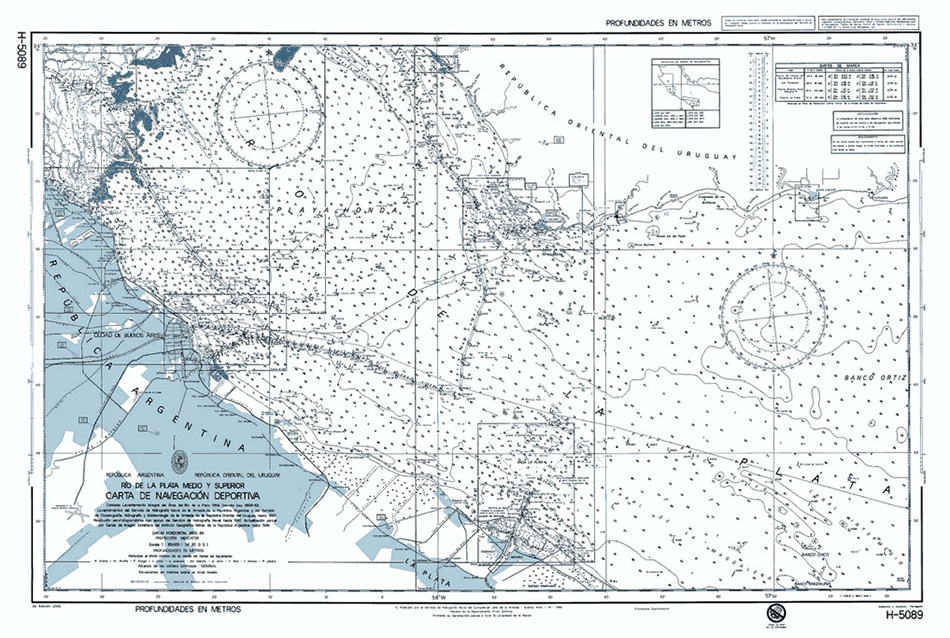

However, having provisionally accepted as valid the illusion of their immutable characteristics, we propose to reflect on the construction of a Rio de la Plata landscape identity.

Identity, the ultimate expression of the local, as a historically and culturally determined imaginary, depends consequently on the specificities present in each of the temporal stages of a territory.

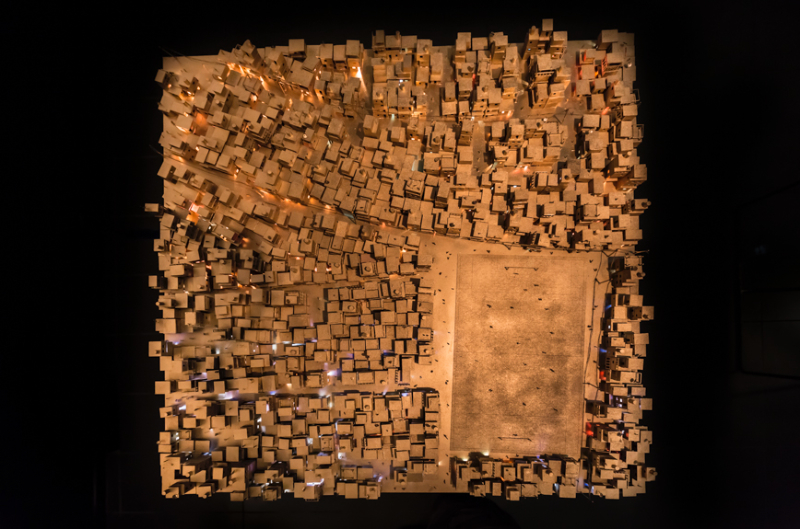

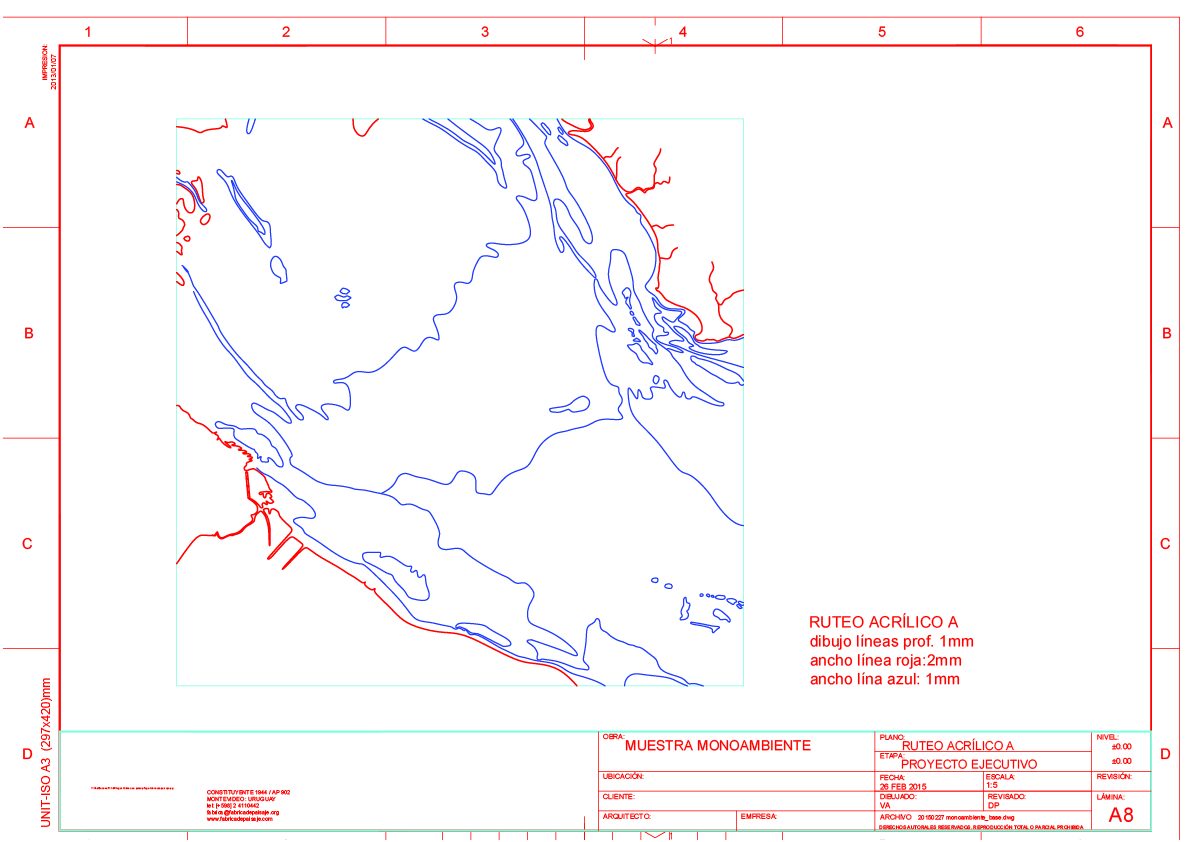

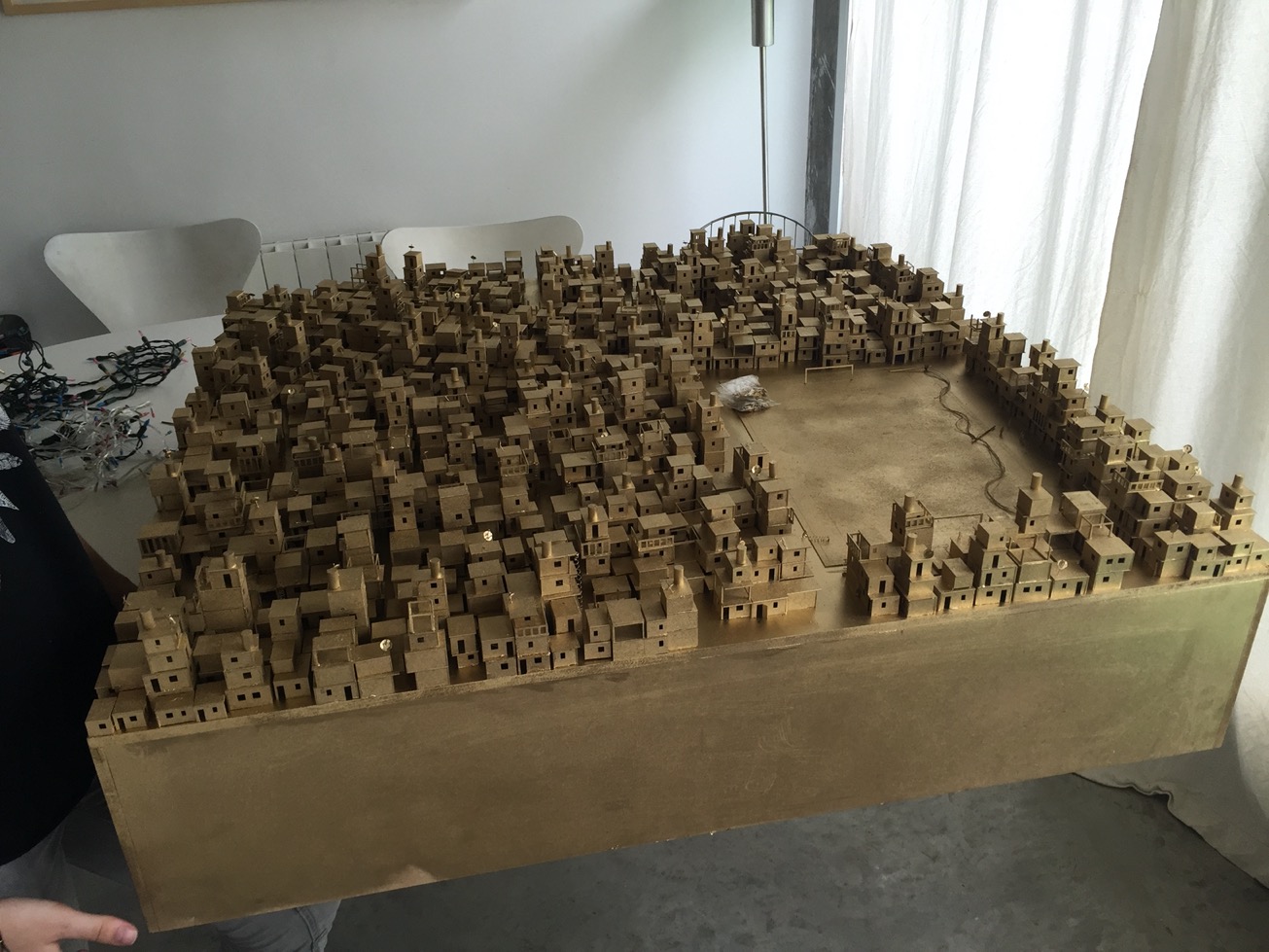

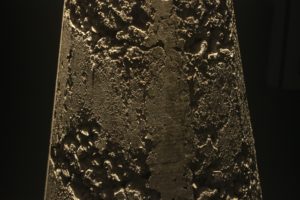

The territory in question, which is part of the second most important hydrographic basin in Latin America, whose final area is the estuary of the Río de la Plata, has different specificities in its final stretches for its opposite margins: accumulation of sediments on the west coast and generation of white beaches on the east coast.

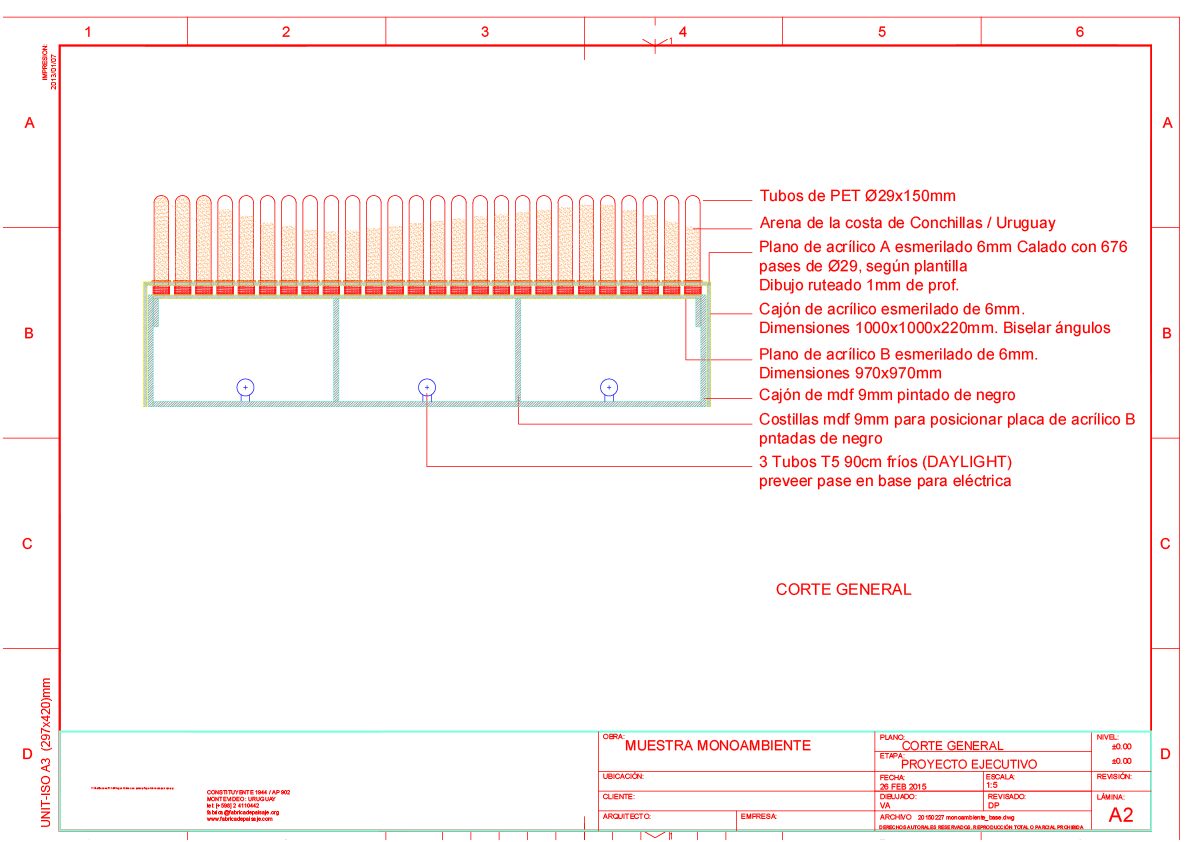

For this reason, in terms of landscape (and tourism to boot), the underlying perception of Uruguay, by extension of its natural spaces, is its sand.

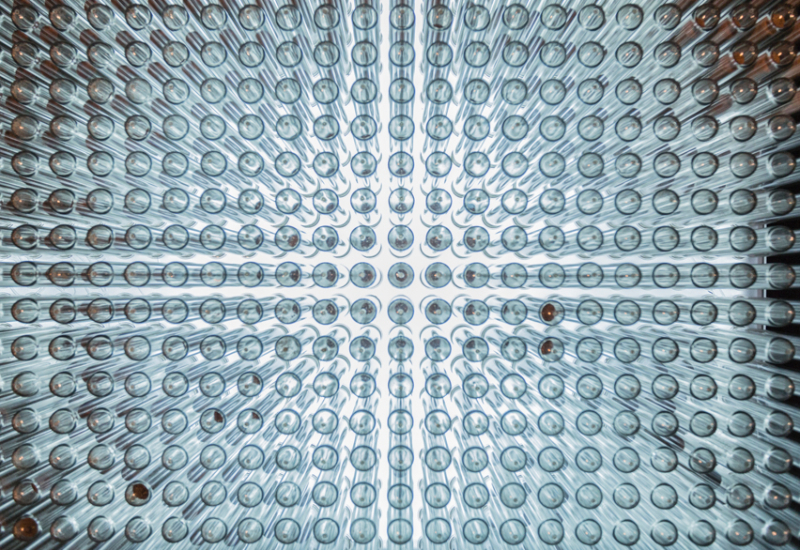

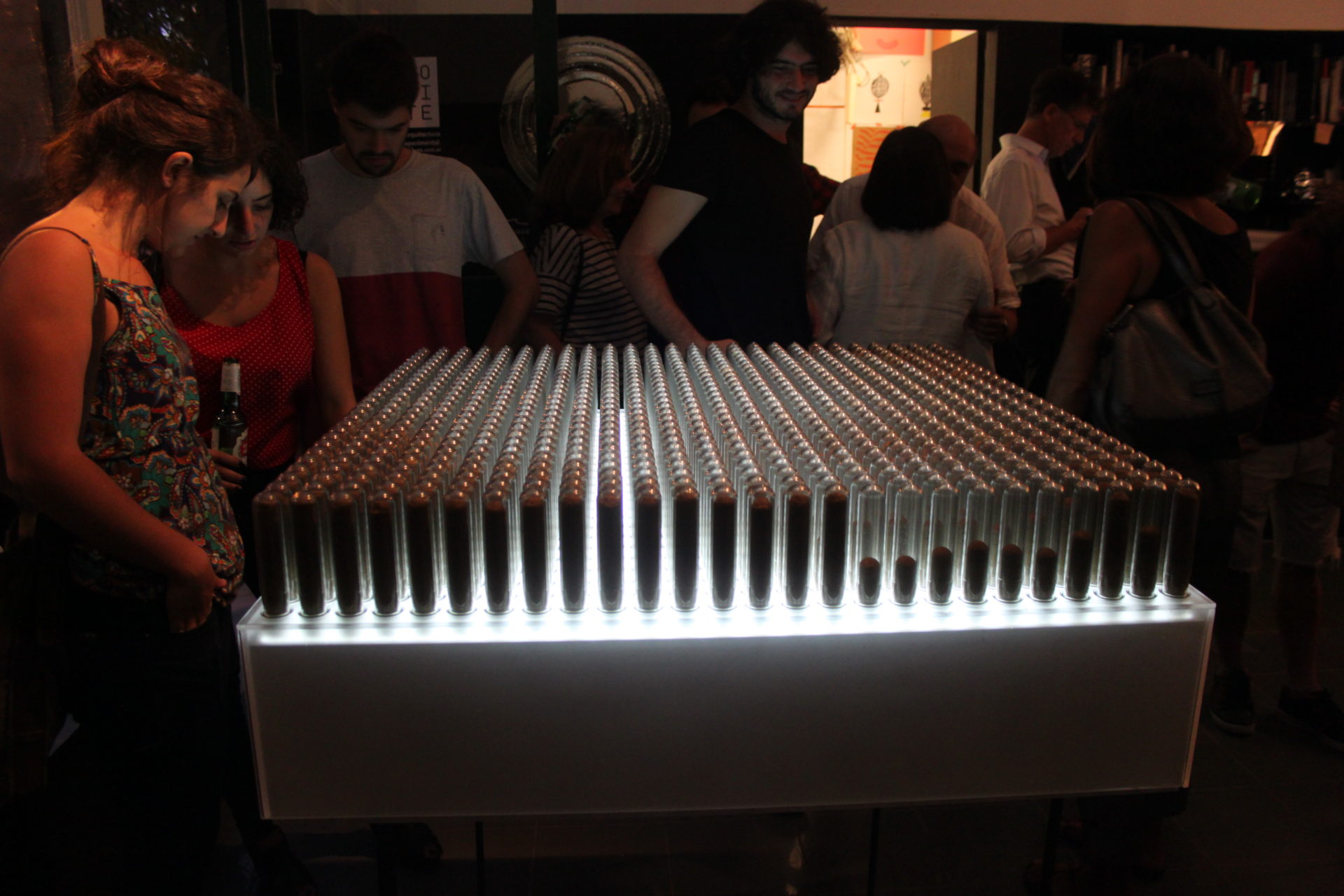

It is worth remembering that, after the industrial revolution, the sustained growth of Buenos Aires during the first decades of the last century turned sand without sediment into a scarce commodity, at the same time as it was essential for the construction in reinforced concrete of both large infrastructures in everyday architectural works.

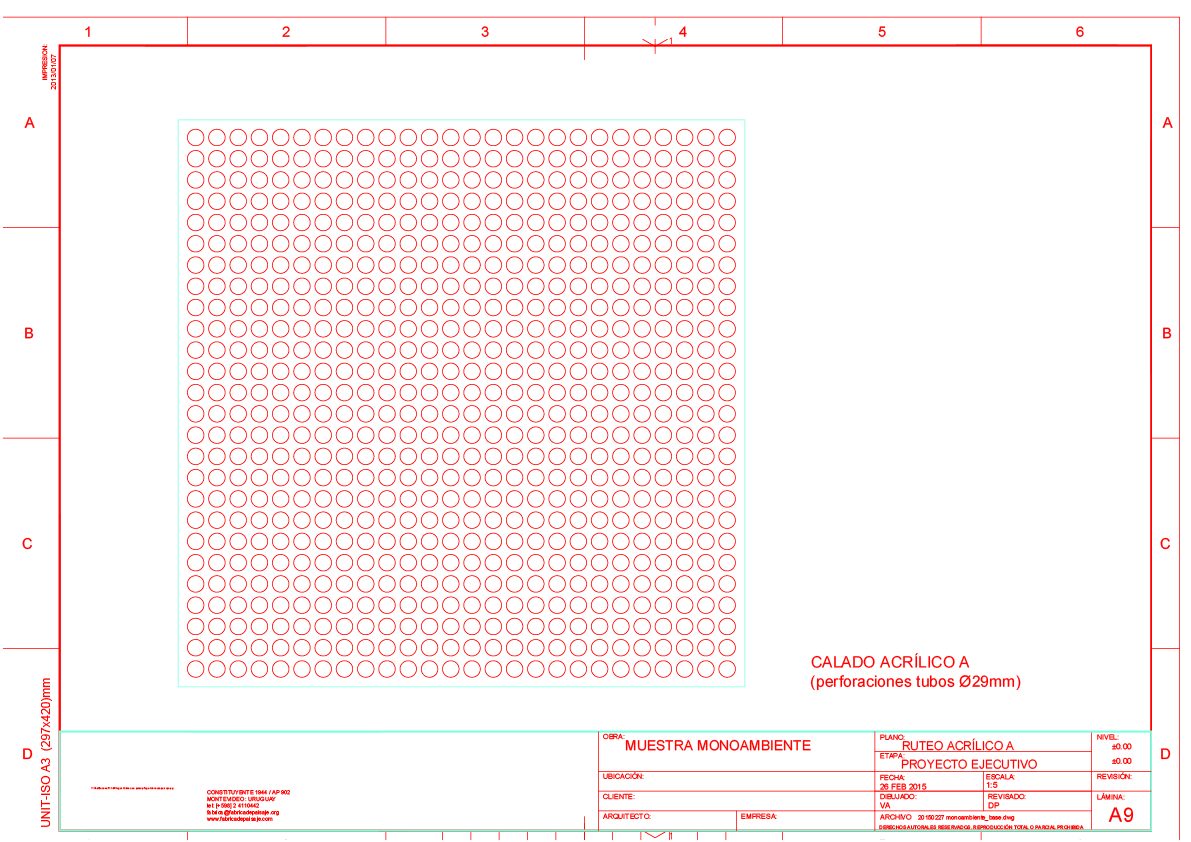

Once the accessible reserves in Argentine territory were exceeded, the proximity to the east bank of the River Plate led to the proliferation of extractive activities in the region of Colonia – Conchillas, which would lead, over time, to drastic transformations in its coastal profile.

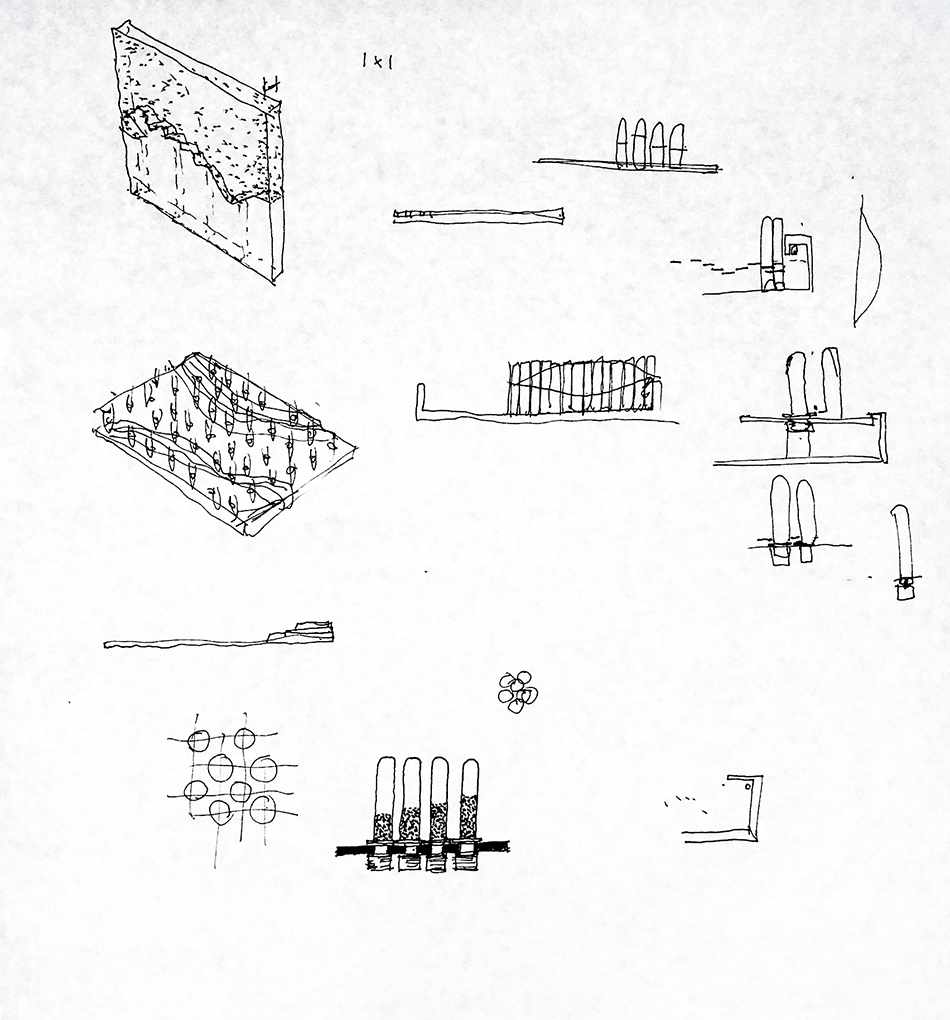

The landscape of the Uruguayan coast is thus, like Adam’s mythical rib, the material from which its companion, the nascent metropolis of Buenos Aires, was elaborated. The open wounds are still there, generating other landscapes, raw material for other developments, and ever-changing testimony to that original creation.