The Gig that Changed the World

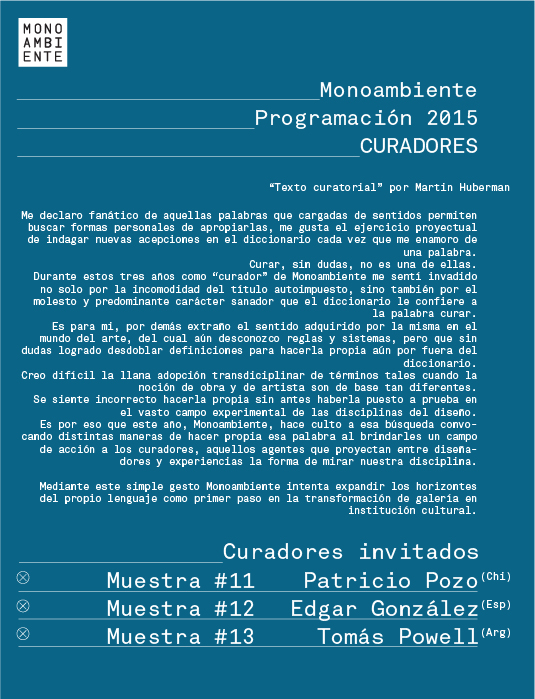

Text by Martin Huberman included for the book 100×100 Diseño en Chile (2019)

edited by Patricio Pozo for Editorial BTG Pactual.

Legend has it that punk rock was born in a mythical evening in June 1976 at the Lesser Free Trade Hall, a neo-classical building in the ruined Manchester, where the Sex Pistols changed music forever. In the improvised bleachers there were only a handful of spectators, among them were Morrissey, some members of the Buzzcocks, a couple of the still self-proclaimed Warsaw (later Joy Division and then New Order) and some other wayward ones who knew how to understand in the insurgence of that sonorous outburst a possible future for their music. The anarchism that that night engraved pure distortion on those present became new ways of thinking about music independently. The fall of the classical industry sparked a need for cultural change, which then became a movement and eventually spilled over into the revival of a decaying city. Before long Manchester had a sound of its own and its musical avant-garde would lead to recognized word wild under the banner of MADCHESTER.

According to the novelist David Nolan that event will be known as The Gig that Changed The World. Some time later I decided to appropriate it to internally name an episode I was part of and witnessed, the arrival of Área (1) in Buenos Aires.

Área had emerged a couple of years earlier, somewhere in 2012, as a festival, but also as a collective of designers aligned in what we could call a parallel practice. In it design was not merely a profession but a key movement in the cultural development of the city and above all of the society it represents.

The force with which Área had crossed the mountain range, initially bathing the shores of Buenos Aires with waves of posts on social networks and specialised blogs, attracted attention. It wasn’t common to see an exhibition of architecture, design and art that was self-generated, that also took a position in the trans-Andean void and that above all dealt with themes and formats that the academy didn’t address and that only a historicist view of practice could bring together. The power of the show was that it spoke to a generation of present designers but above all it showed future ones how it was possible to organise themselves to generate new scenarios of discussion, meeting and exhibition simply by joining forces. The autarchism infected the rehearsal that curated the show and the pieces presented were dismantled in processes while the participants were forced to leave the comfort zone provided by the idealism of the finished work and turn back to revisit themselves. The gesture was assimilated to undressing. Only then, in a natural state, could they make contact with each other and with others.

Demystifying, making transparent, undressing and rehearsing the fragility of the processes.

Disciplinary anatomy, that was the genesis of Area One (1).

A year later and still naked, Area Two (2) would rehearse on the garments that design could conquer. Like a drag queen entering the disco hanging from a ball of mirrors, pushing at the edges. To inhabit the edge, to build from the limit, to take charge of uncertainty, to seize the void for an instant, like that strange typological coexistence between the void that a seventies punky pogo and a glamorous danceoff from the disco era need equally. It was on that edge that the second version of what was already being raised as a system of cultural production was forged.

Curing vertigo, in the distance I felt twinned.

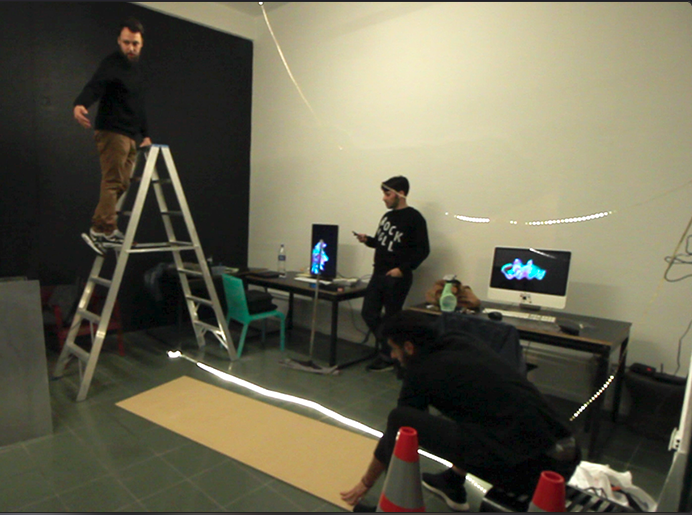

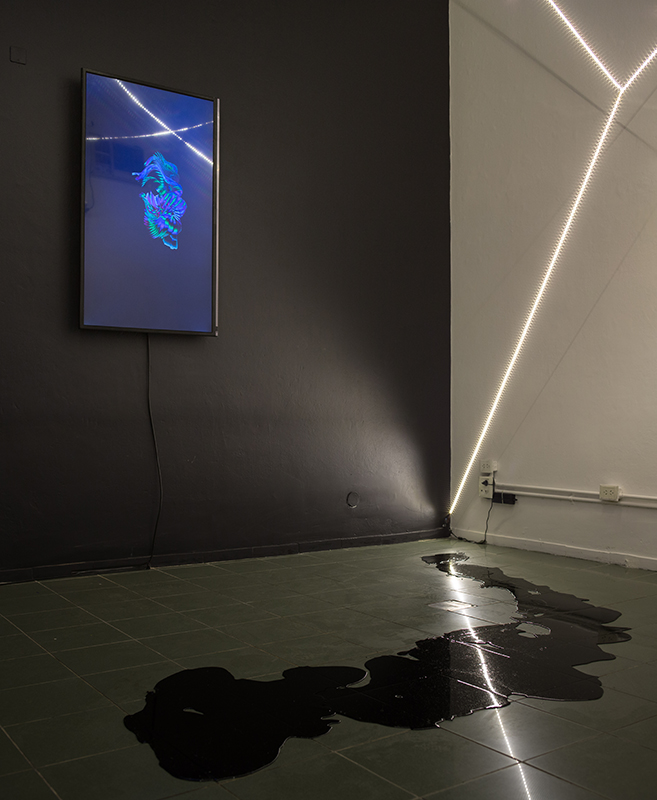

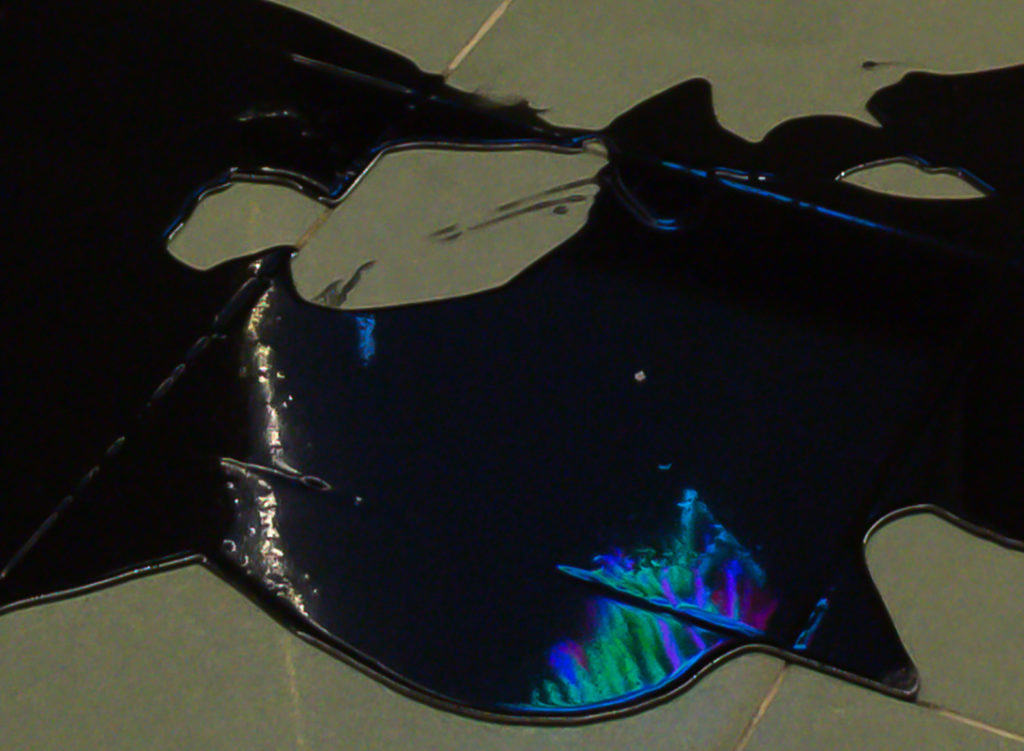

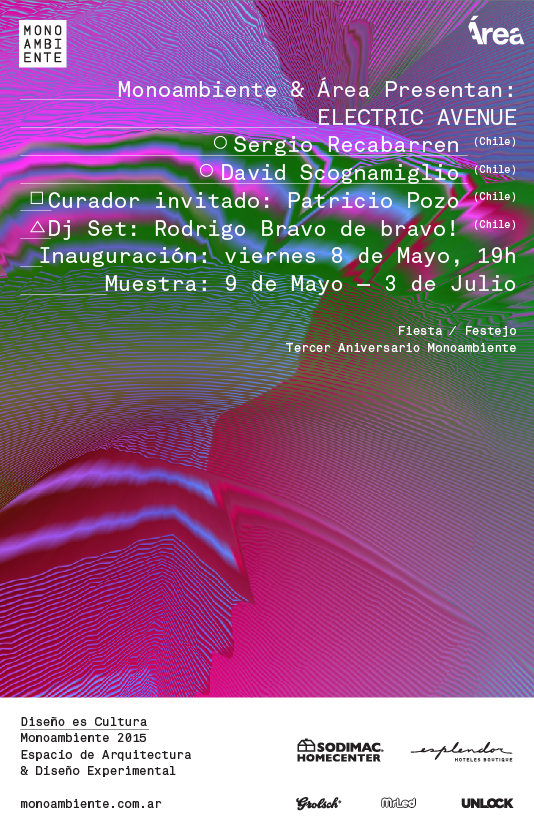

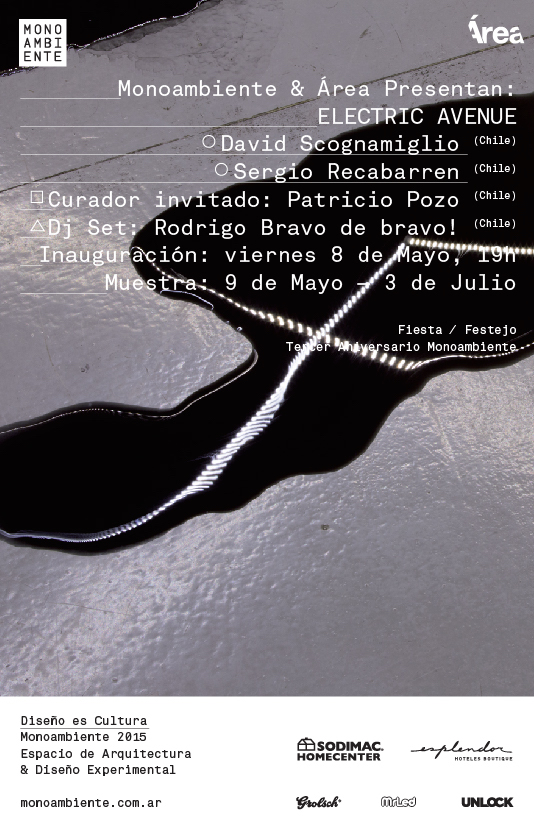

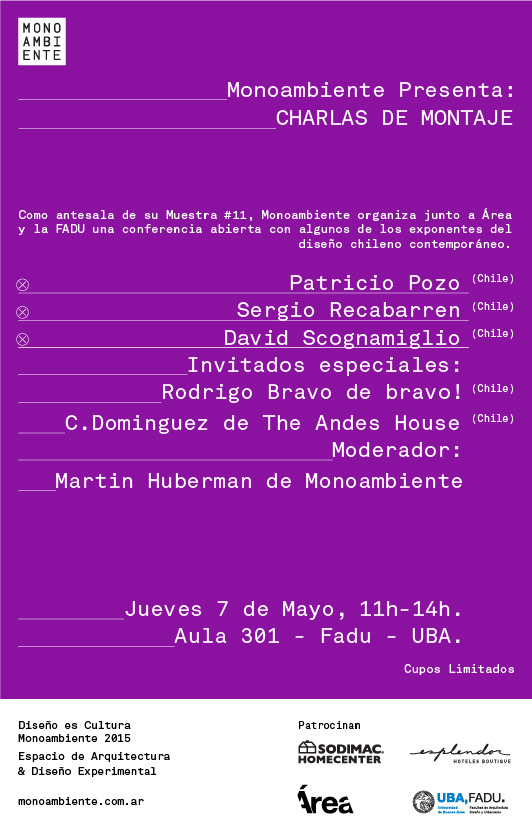

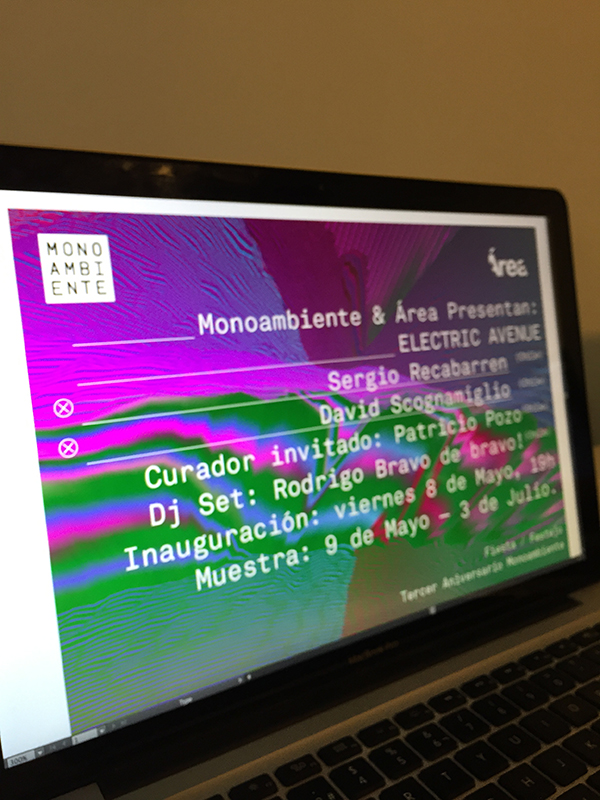

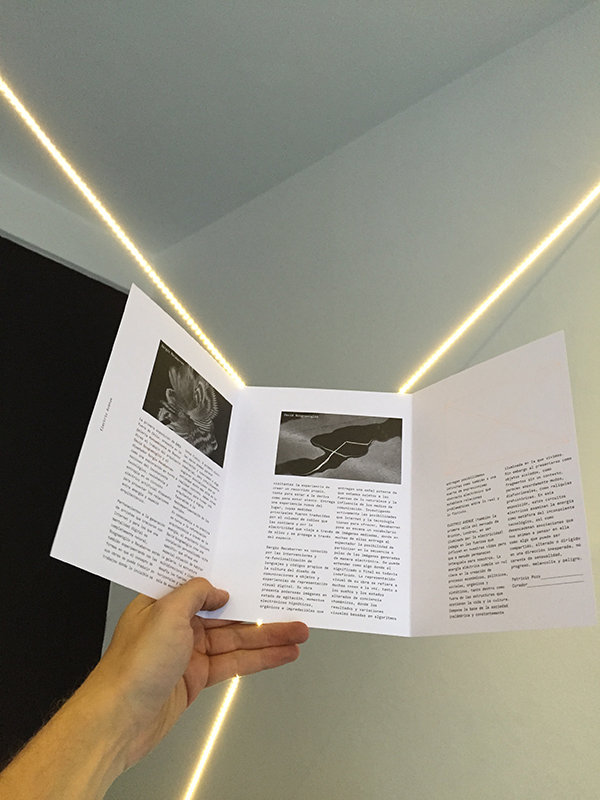

After all, it was this spirit that was at the origin of Monoambiente (3), whose first international exhibition was Chilean, hosting in 2013 works made specifically by The Andes House and Cristóbal Palma (4). That first attempt to forge a transcordilleran bridge/tunnel with Chile needed a second itinerancy to consolidate itself. It wasn’t until early 2015 that as part of a cycle of young guest curators that the invitation fell to “al Pato Pozo” to take over the space. Making use of the independence that linked both projects, Monoambiente 11 was also Área Tres (5) and with a patriotic gesture a band of Chilean designers crossed the cordillera to present Electric Avenue, a digital analogue celebration of electrified life.

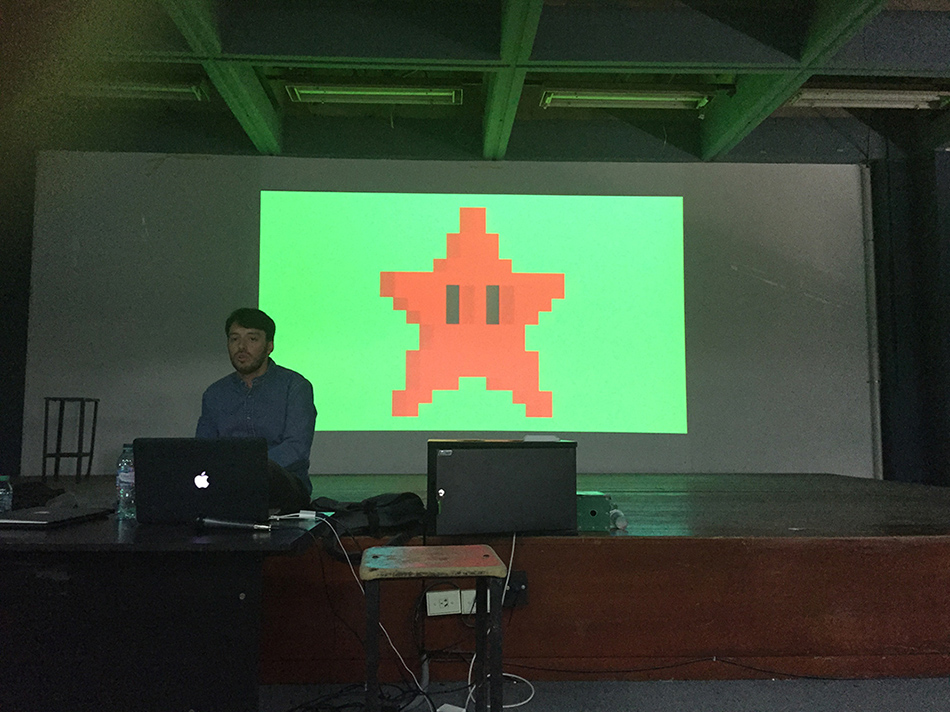

A breath of management led me to understand that in that handful of colleagues it was possible to paint with clarity the Santiago design scene that had ousted the Buenos Aires scene as the most thriving, ordered and prolific, in the eyes of the media and the strongest disciplinary scenes on the planet. It was imperative to make this feat a public event, at least one of many, and so we organised a conference in the second largest hall of the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Urbanism of the University of Buenos Aires, with a capacity for 330 spectators. It was clear that we expected with blind idealism a room full of students who had to escape from their courses to listen to the Chilean New Wave. The minutes passed and the hall remained empty. We looked at each other somewhat incredulous, somewhat frustrated, but above all complicit. Then, out of nowhere, Arturo Peruzzotti (architect, illuminator and factotum of Monoambiente #09 (6) arrived, the silence was broken into pieces and we decided to start, in spite of everything, the six presentations. The talk would be for us, an eternal anecdote that would die among a few, seven to be exact. To make, to push, to build, has these details and the brief experience on both sides of the mountain range had taught us that you always have to go on, even if only one spectator comes.

Then the door opened, slowly, somewhat fearfully, as if asking permission, and behind it appeared the figure of the maestro Ricardo Blanco (7), panting and somewhat worried that he had missed it, he asked:

“The talk of the Chileans… Is it here?

“Come in, maestro, we’ve been waiting for you”.

His presence filled the emptiness, the tireless hunger to know, to know, to investigate, to be glued to that crazy rhythm that is design. Blanco, in his seventies, still wanted to learn.

Six speakers and two spectators.

For those of us who were there, the recital was a full house.

This is how The Gig that Changed the World was conceived in a South American version.

Martin Huberman

PS: The show, the party on the pavement, the joint in the gardens of the mythical Ølsen restaurant, the trip to Madrid with Área Cuatro, will be left for the book about post punk…

1.- Area One – Processes . Factoría Italia – January 2013.

2.- Area Two –

Monoambiente is the first gallery in South America specialising in architecture and design, founded in 2011 by Martin Huberman in the Complejo Los Andes in the neighbourhood of Chacarita. Huberman, author of this text, is still at the forefront of the project today, advocating the cultural contribution that these disciplines make to their communities.

Monoambiente 06 – Paso de The Andes House & I am a Photo by Cristóbal Palma, curated by Martin Huberman – Buenos Aires. 2013

Monoambiente 11 / Àrea Tres – Electric Avenue, David Sconamiglio and Sergio Recabarren, curated by Patricio Pozo. Buenos Aires. 2015

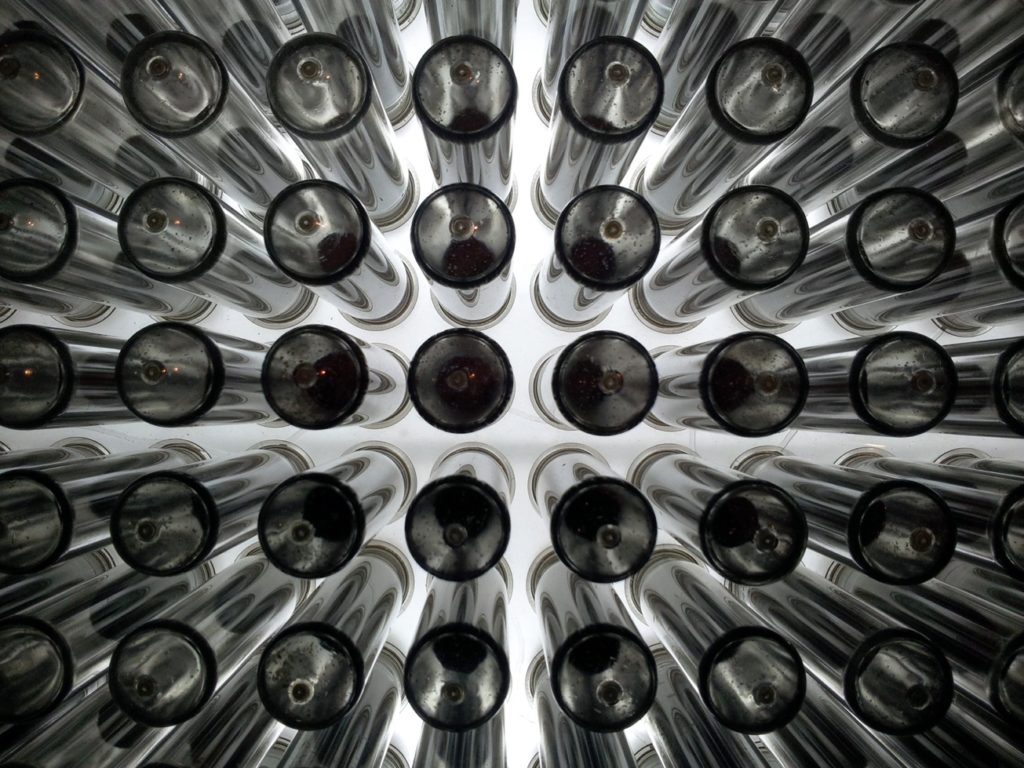

6.- Monoambiente 09 – Cones by Arturo Peruzzotti and Mariano Clusellas curated by Martin Huberman. Buenos Aires. 2014

Wikipedia defines Ricardo Blanco as a renowned Argentine architect and designer, but in reality I dare to call him a legend. His designs transcended borders to become part of the global scene, he founded successive companies and furniture factories in which he produced his designs and those of other prominent designers. Finally, until the year of his death in 2017, Blanco taught at various universities, but mainly at the University of Buenos Aires, where for years he directed the Industrial Design course. Today, to speak of Ricardo Blanco is to speak of high-flying Argentine design.